Nola Bred, Nola Fed: An Interview with Ralph Brennan

From L to R: Ralph Brennan, Ella Brennan, Dottie Brennan, Lally Brennan and Ti Martin

I am sitting upstairs at Brennan’s Restaurant in the Queen’s Room, and before Ralph Brennan says a word, I already feel like I know something about him. Not because of his résumé. Not because of the list of restaurants. Not because of the legacy.

Because this room feels familiar.

Ralph Brennan did not grow up aspiring to own restaurants. He grew up inside them. Brennan’s on Royal Street was part of his childhood geography. He wandered the halls, watched cooks work, watched servers move through the dining rooms, and watched guests arrive dressed for moments that mattered. Long before balance sheets or business plans entered his vocabulary, he understood something more important. Restaurants are where life happens.

Weddings. Engagements. Family celebrations. Quiet dinners that turn into traditions.

Today, Ralph serves as president of the Ralph Brennan Restaurant Group, overseeing Brennan’s, Napoleon House, Red Fish Grill, Ralph’s on the Park, Café NOMA at the New Orleans Museum of Art, and Jazz Kitchen in Downtown Disney. Sitting across from him, it becomes clear he does not think in terms of portfolios. He thinks in terms of rooms. Rooms that must remain useful. Rooms that must continue absorbing people’s stories.

Family Roots and Learning the Work

As Ralph begins talking about his family, the pattern reveals itself quickly.

No shortcuts. Just work.

The Brennan restaurant story begins with Ella Brennan and her siblings, a large Irish Catholic family who found their footing in the French Quarter in the mid 20th century. Ella went to work for her brother Owen at the Absinthe House despite her mother’s concerns about the setting. While her friends attended finishing school, Ella spent her evenings learning hospitality inside the Quarter.

In the late 1940s, Owen took over a restaurant across from Arnaud’s after being goaded by Count Arnaud Cazenave that an Irishman could never run a French restaurant. He accepted the challenge. Brennan’s Vieux Carré was born. By 1956, the family had renovated and opened the building at 417 Royal Street, parading through the streets to celebrate.

Ralph Brennan, born in 1951, grew up immersed in this world.

His first paid job came in high school in the upstairs prep kitchen at Brennan’s.

“I was probably a sophomore in high school, and that was my first job in the restaurant business.”

He peeled shrimp and deboned chickens. After one especially long day processing chickens, he went home and discovered chicken was for dinner. He left and bought a hamburger. His aunt noticed. The following week she moved him to the line, where he learned to poach eggs and make hollandaise for Eggs Benedict and Eggs Hussarde.

Summers were spent delivering 35 pound bags of potatoes for his father’s supply company, carrying them through back doors of seafood restaurants across New Orleans. Later, he worked seven days a week at Brennan’s Friendship House in Gulfport, Mississippi, a family style seafood restaurant that ran full throttle between Memorial Day and Labor Day.

Listening to Ralph tell these stories, I realize nothing about his path was designed. It was earned.

Detour, Training, and a Return

Ralph earned degrees in economics and business from Tulane and hoped to enter the family business, but a split within the Brennan family in the mid 1970s left no immediate opening. His aunt sat him down and told him plainly.

“I don’t have a place for you right now. You need to get a job.”

So he did.

He joined Price Waterhouse, earned his CPA, and learned how companies actually operate. He spent time working in Canada during an oil boom, gaining exposure to fast growing businesses under pressure.

The call back came in 1980.

“It was Christmas night of 1980 at my parents’ dinner table, and I was seated next to Ella and she leaned over to me and said, call me. I want you to come back in the company.”

But Ella did not simply invite him back. She insisted he be trained.

Ralph spent time at a language school in southern France, then three months in Paris at a culinary program, followed by work at the 21 Club in New York rotating through the wine cellar, kitchen, and private events. Not to become a chef, but to understand kitchens, systems, and standards.

When he returned to New Orleans, he was sent to Mr. B’s Bistro as night manager, then general manager. It became his proving ground.

In 1986, Ralph and his sister Cindy purchased Mr. B’s. From there came Red Fish Grill on Bourbon Street, Jazz Kitchen Coastal Grill & Patio in California at Disney’s invitation, and Ralph’s on the Park in Mid City.

Each time he describes opening a restaurant, the language is consistent. Not expansion. Not conquest. Belonging. Create restaurants that feel like they were always supposed to be there.

Stewardship Over Reinvention

I tell Ralph I stopped at Napoleon House the day before our interview. Muffuletta. Red beans. Pimm’s Cup. He smiles.

In 2015, the Impastato family approached Ralph about purchasing Napoleon House, which they had owned for more than a century. They wanted a buyer who would not turn it into something else. Ralph agreed.

He honored the recipes, the systems, and the rhythm. One person still makes the red beans every day.

Ralph explains his philosophy simply.

“We focus on delivery. Our team members are empowered to do whatever it takes to make our guests happy. Our company motto is, make our guests happy and enjoy the thrill of doing so.”

He often refers to his restaurants as “the house of yes.”

“And if we make a mistake, we fix it and we do whatever it takes to fix it. When they leave and we want all of our guests to leave with a good experience, even with a hiccup or so, and we fix it, they become ambassadors for the restaurant.”

That same mindset guided Ralph when he quietly reclaimed the Royal Street building that houses Brennan’s after his cousins’ business fell into bankruptcy. The building was in worse condition than expected. A six month renovation became 16. The restaurant closed completely.

When Brennan’s reopened, guests told him the same thing.

It feels exactly the same.

I can confirm.

A Life Shaped by Place

Ralph has lived through 9/11, hurricanes, recessions, and COVID. During the pandemic, every restaurant closed in a single day. Revenue dropped to zero. What mattered most to him was keeping his leadership team intact.

“I made a point based on the lessons we learned from Hurricane Katrina that we worked very hard to keep our management team in place, because I knew it was going to end. I knew we were going to come back at some point.”

Today, Ralph keeps his personal life simple. Light meals at home. Salads, fish, chicken. He tastes constantly at his restaurants.

Each year on his birthday, he invites his grandchildren to Creole Creamery for ice cream with printed invitations. His order is chocolate peanut butter chip. His snowball is nectar cream from Plum Street Snowballs.

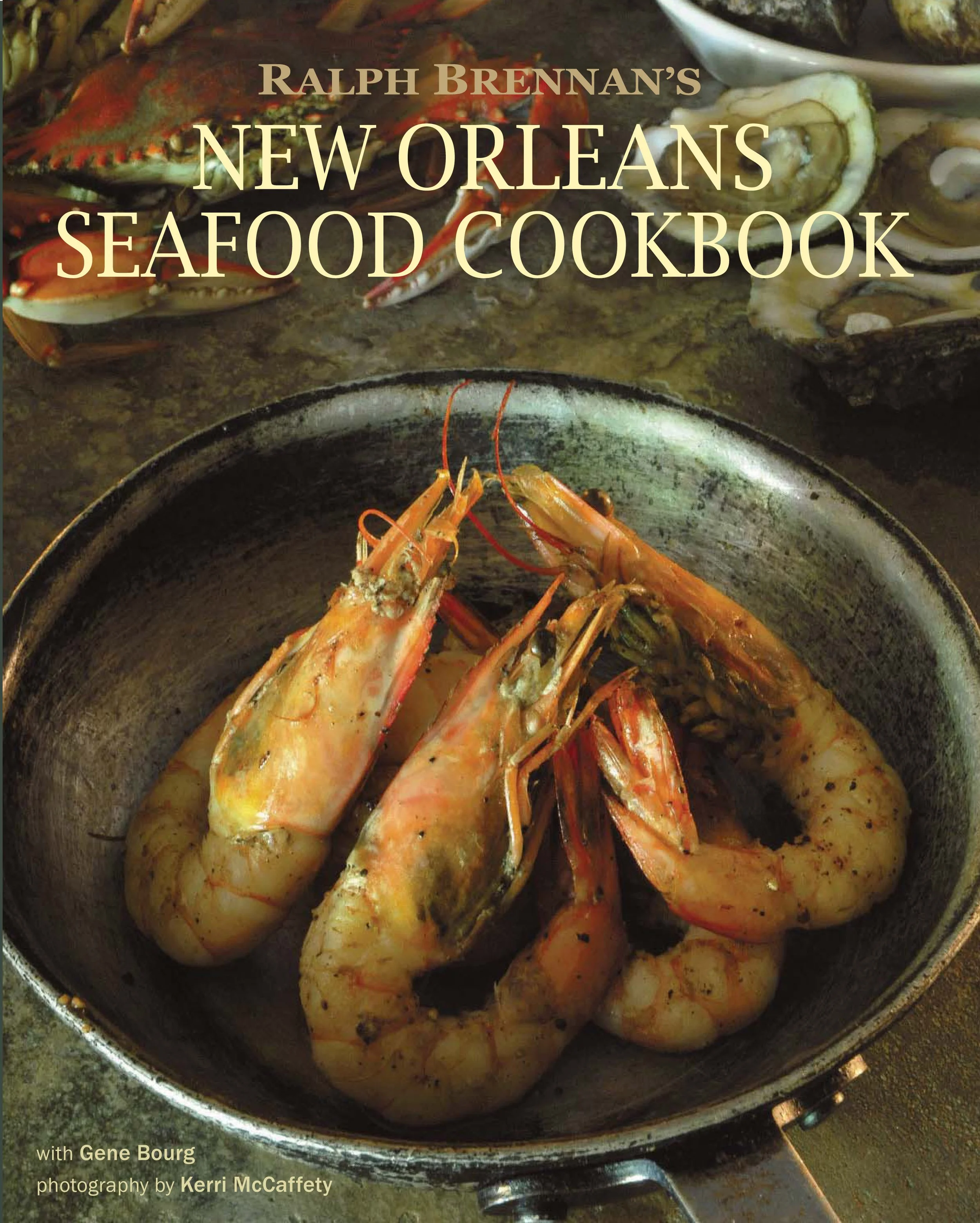

Near the end of our conversation, I share a family story. When Ralph released his seafood cookbook, my siblings and I jokingly brainstormed an alternate title.

“Recipes That Made Me Ralph.”

It never reached his desk. Probably for the best.

But the moment captures something important.

Ralph never wanted to be the headline.

He wanted the restaurants to be.

I suspect that mindset is also why Ralph continued working with my father on project after project for decades. Not because of ego. Because of trust.

Some restaurateurs chase novelty. Others chase scale.

Ralph Brennan has spent his life pursuing continuity.

Making sure New Orleans’ most important dining rooms remain open, familiar, and worthy of the memories created inside them.

Not by reinventing them.

But by taking care of them.